“No way, no way,” Garner says, smiling and winking and raking in the chips with his big, meaty right hand. “What we got here is an I-treat-you-like-a-king interview. We’re talking your basic royalty on the road. Man came all the way from that behavior sinkhole New York City to talk to me, boys, so I’ll have to do some work. I don’t know why anybody would want to know what the hell I have to say anyway, but as long as he’s here, we’re going to treat him right.”“Just make sure you teach him Jerry’s Rules,” says Dave, a muscle-bound kid with a big, innocent face. “I still don’t understand that goddamned game.”“In good time,” Garner says. “All in good time, Dave. Just make sure you get us out there to the location in that damned snow tomorrow, okay?”

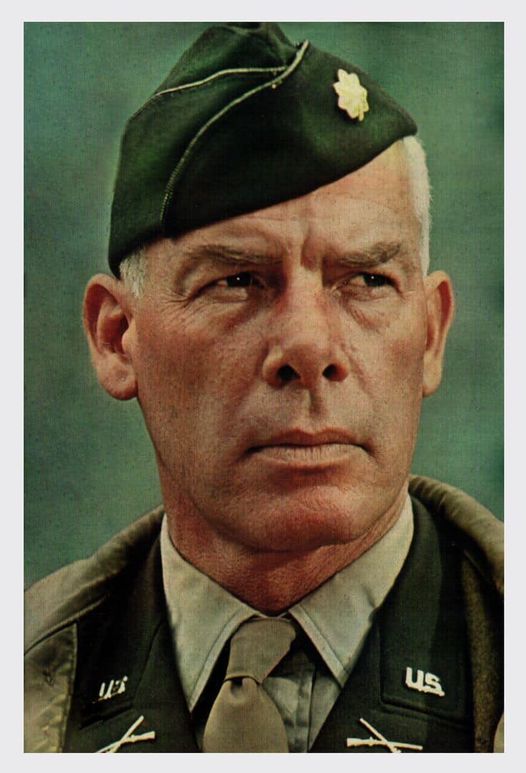

As I walk into James Garner’s suite at the Palisades Hotel in Vancouver, British Columbia, I suddenly feel as though I’m the Dude From the East accidentally strolling into the back room in Black Bart’s Saloon. There, sitting around a table in the kitchen, is Bret Maverick himself, surrounded by four other poker-playing rascals, and all of these boys are big. We’re talking teamster big, with hair that looks like windblown bushes and sweaters that bulge with muscles, and not your smooth, sinewy account-exec Nautilus muscles, either. No, these guys are North Country big, with muscle and flab and big, flat faces, and they’re all smiling at none other than Gentleman Jim Garner himself, who turns and looks at me with that Jim Rockford “Awww hell, Angel” smile and says, “Now isn’t this just my luck. Just when I’m getting ready to take these suckers for every dime they got in a fast little game of Jerry’s Rules, I have to do this damned interview. Well, hell, on the other hand, maybe we got us here what you call your one more basic pigeon. Get yourself a drink of wine from the box in there, Robert, while I finish up this hand.”He’s up here filming Joseph Wambaugh’s novel The Glitter Dome for HBO, and Garner is all smiles as he invites me in. There is that born confidence man’s charm in his voice. “You get your wine, Robert?” Garner asks as he laughs and deals the boys another hand. “You know these journalists, they do like their booze.

”“Now just a minute,” I say. “Is this going to be one of these star-insults-the-press interviews?” Garner had already informed me that he does only one interview a year, and this is it. (“Hell,” he’d pointed out, “I don’t even eat with my press agent.”)“No way, no way,” Garner says, smiling and winking and raking in the chips with his big, meaty right hand. “What we got here is an I-treat-you-like-a-king interview. We’re talking your basic royalty on the road. Man came all the way from that behavior sinkhole New York City to talk to me, boys, so I’ll have to do some work. I don’t know why anybody would want to know what the hell I have to say anyway, but as long as he’s here, we’re going to treat him right.”“Just make sure you teach him Jerry’s Rules,” says Dave, a muscle-bound kid with a big, innocent face. “I still don’t understand that goddamned game.”“In good time,” Garner says. “All in good time, Dave. Just make sure you get us out there to the location in that damned snow tomorrow, okay?”The next day, after a morning of playing backgammon and shooting craps with Garner and his stand-in/best buddy for thirty-seven years, Luis Delgado, I’m in Garner’s van, heading across Vancouver for a graveyard scene.

It’s getting cloudy and dark out, and Jim Garner is talking about his past, honesty and Hollywood.“You see,” he says, flipping down his shades and looking out at the streets, “I was raised in a place where a man’s word was his bond. Oklahoma. Oh, sure, we had our hustlers there too, but for the most part people were honest, took care of one another. If a man lied, it was usually transparent, because the norm was to tell the truth. But in L.A. people live the lie. They’ll look you right in the eye and lie to you. They lie even when there’s no reason to. I don’t understand those people. They’re too devious for me. I don’t trust any of them anymore. They’ve taken the heart out of it for me, and I used to really love this business.”I ask if he’s referring to the multimillion-dollar lawsuit against Universal over The Rockford Files, in which Garner is suing to retrieve profits from the series.“Some guys are professional, too professional, so they get slick and use the same old tricks. But Jim is working on making it real, rougher around the edges.”

“Yeah, among other things. Our company, Cherokee Productions, was supposed to get a 38 percent share of the profits. We brought that series in only seven days over schedule in five and a half years—no other television show can match that record for even one year. The show was a big, big hit. I figure they’ve stolen about 25 million dollars from me, and that’s a hell of a lot of money.”He then begins to patiently explain the elaborate and varied tricks accountants can play to somehow conclude that a show that was a hit for six years, and is still in syndication, didn’t earn a dime and is, in fact, $9.5 million in debt. “I don’t know if I’ve got the guts to resist the out-of-court settlement when they offer me a whole bunch of money to call it off,” Garner admits.“Is it worth all the mental aggravation?” I ask.“Now you’re talking like them,” Garner says, and there’s steel in his voice. “They figure to wear you down. But damn, it’s not just that they have my money, it’s also the principle of the thing. It’s wrong.”There’s a finality to the word wrong, and I have to smile. I think of Martha, a southern lady I know who’s a secretary in Baltimore. When I told her I was going to interview James Garner, she said, “You tell him he has an honest face and he’s the only damned movie star I’d move back into a trailer with, you hear?”At a freezing suburb outside Vancouver that has been dolled up to resemble L.A., Garner gets dressed to play a tough scene. He plays a burned-out detective in The Glitter Dome.

A buddy has been killed, and Garner has to stand at the funeral in the “rain” (supplied by off-camera hoses with sprinklers attached) and look as though he’s been beaten down by exhaustion and drink and fatigue. As I wait for him to change his clothes I talk to Stuart Margolin, the director. He’s best known, though, as Angel, Jim Rockford’s squealing, bitching, cowardly but lovable buddy-nemesis on The Rockford Files.We huddle up in a truck cabin, eat some cold chili and talk about Garner’s acting.“He’s getting better and better as an actor,” Margolin says. “I mean, some guys are professional, too professional, so they get slick and use the same old tricks. But Jim is working on making it real, rougher around the edges. The next ten years should be interesting. He’s turning the corner into what you call the leading character man. He’s going for more experimentation, and he’s brought a reality all his own to this part. You watch these scenes, and you’ll see what I mean.

This isn’t Maverick.”A few minutes later I watch Garner standing on the freezing infield of a Vancouver playground. The water is coming down on him, and the camera closes in, and there is pain, disgust, weariness, that does look different from anything I’ve seen from him in the past. It’s the face of an older, hurt man, and I think that maybe, unconsciously, he’s using the lawsuit against Universal to summon these feelings of disgust and anger. But whatever is pushing him forward, it’s obvious that he’s going for something different here, something that reaches the gut in a deeper way than charm.Now, in the darkness, we’re riding across Vancouver. Our friend Dave the driver has stopped by the van and assured us there’s not going to be any snow, but it’s already falling, great thick flakes. All the world’s a great, soft stage, and only the hum of the van’s engine cuts through the night as Garner rides shotgun and Luis and I sit in the back in a warm, comfortable and friendly haze.“I read somewhere that you never let your price get too high for films,” I say. “Why’s that?”“Well,” Garner says, turning around and putting one leg up on the tool hump, “in Hollywood they have this terrible thing: You can’t ever let your price go down When Lee Marvin put his price up to a million dollars a picture, he found it harder to get work. I didn’t want to cut myself out of work, so I never let it get that high. I mean, if a picture is really good, I’ll do it for practically nothing, take a little profit on the back end.”“Have you ever really done that?” I ask.At 55, his knees are shot, the result of several operations and arthritis, but otherwise he looks great, and later I ask him if he works out at all. After an appropriate pause, he says, “The only time you’ll see me jogging is if somebody is chasing me—and he better be big, or I won’t even run.”