At the Pasadena Playhouse school, Bronson improved his diction, supporting himself by selling Christmas cards and toys on street corners. Studio scouts saw him at the Playhouse and he was cast as a gob in the 1951 service comedy “You’re in the Navy Now” starring Gary Cooper.As Charles Buchinsky or Buchinski, he played supporting roles in “Red Skies of Montana,” “The Marrying Kind,” “Pat and Mike” (in which he fell victim to Katharine Hepburn’s judo), “The House of Wax,” “Jubal” and other films.

In 1954 he changed his last name, fearing reaction in the McCarthy era to Russian-sounding names.Bronson’s first starring role came in 1958 with an eight-day exploitation film, “Machine Gun Kelly.” He also appeared in two brief TV series, “Man with a Camera” (1958) and “The Travels of Jamie McPheeters” (1963).His status grew with impressive performances in “The Magnificent Seven,” “The Great Escape,” “The Battle of the Bulge,” “The Sandpiper” and “The Dirty Dozen.” But real stardom eluded him, his rough-hewn face and brusque manner not fitting the Hollywood tradition for leading men.Alain Delon, like many French, had admired “Machine Gun Kelly,” and he invited Bronson to co-star with him in a British-French film, “Adieu, L’Ami” (“Farewell, Friend”). It made Bronson a European favorite.Among his films abroad was a hit spaghetti western, “Once Upon a Time in the West.” Finally Hollywood took notice.Among his starring films:

“The Valachi Papers,” “Chato’s Land,” “The Mechanic,” “Valdez,” “The Stone Killer,” “Mr. Majestyk,” “Breakout,” “Hard Times,” “Breakout Pass,” “White Buffalo,” “Telefon,” “Love and Bullets,” “Death Hunt,” “Assassination,” “Messenger of Death.”The titles indicate the nature of the films: lots of action, shooting, dead bodies. They were made on medium-size budgets, but Bronson was earning $1 million a picture before it was fashionable.His most controversial film came in 1974 with “Death Wish.” As an affluent, liberal architect, Bronson’s life is shattered when young thugs kill his wife and rape his daughter. He vows to rid the city of such vermin, and his executions brought cheers from crime-weary audiences.

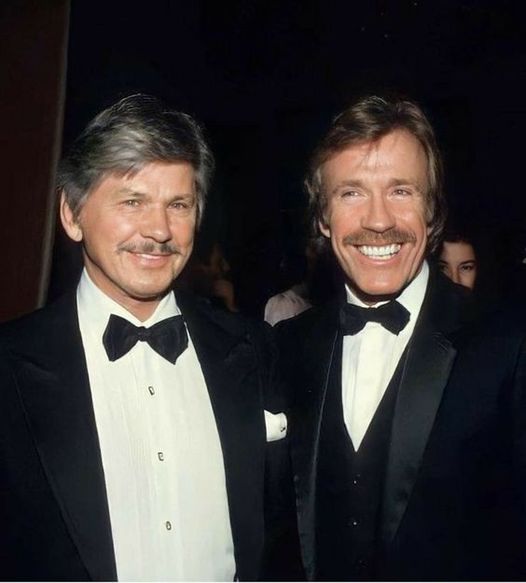

The character’s vigilantism brought widespread criticism, but “Death Wish” became one of the big moneymakers of the year. The controversy accelerated when Bernard Goetz shot youths he thought were threatening him in a New York subway.Bronson made three more “Death Wish” films, and in 1987 he defended them:“I think they provide satisfaction for people who are victimized by crime and look in vain for authorities to protect them. But I don’t think people try to imitate that kind of thing.”Bronson could be as taciturn in interviews as he appeared on the screen. He remained aloof from the Hollywood scene, once observing, “I have lots of friends and yet I don’t have any.”His first marriage was to Harriet Tendler, whom he met when both were fledgling actors in Philadelphia. They had two children before divorcing.In 1966 Bronson fell in love with the lovely blonde British actress Jill Ireland, who happened to be married to British actor David McCallum. Bronson reportedly told McCallum bluntly: “I’m going to marry your wife.”The McCallums were divorced in 1967, and Bronson and Ireland married the following year. She co-starred in several of his films.

The Bronsons lived in a grand Bel Air mansion with seven children: two by his previous marriage, three by hers and two of their own. They also spent time in a colonial farmhouse on 260 acres in West Windsor, Vt.Ireland lost a breast to cancer in 1984. She became a spokesperson for the American Cancer Society and wrote a bestselling book, “Life Wish.” She followed with “Life Lines,” in which she told of her struggle to rescue her 27-year-old son, Jason McCallum Bronson, from drug addiction. He died of an overdose in 1989, and she died of cancer a year later.